The Silent Epidemic: Understanding and Treating Loneliness in the Modern Age

Loneliness is increasingly being recognized as a significant psychological and public health concern, rivaling smoking and obesity in its impact on morbidity and mortality. Despite its prevalence, loneliness often goes unspoken in clinical settings, hidden beneath the surface of depression, anxiety, or somatic complaints. As psychology professionals, we are uniquely positioned to identify, understand, and intervene in this pervasive yet silent epidemic.

Defined as the subjective experience of social isolation, loneliness is not merely a function of being alone. Clients may be surrounded by people and still feel profoundly disconnected. It is this perceived gap between desired and actual social connection that makes loneliness psychologically distressing. Research has consistently linked chronic loneliness to increased risk of cardiovascular disease, cognitive decline, weakened immunity, and early mortality.

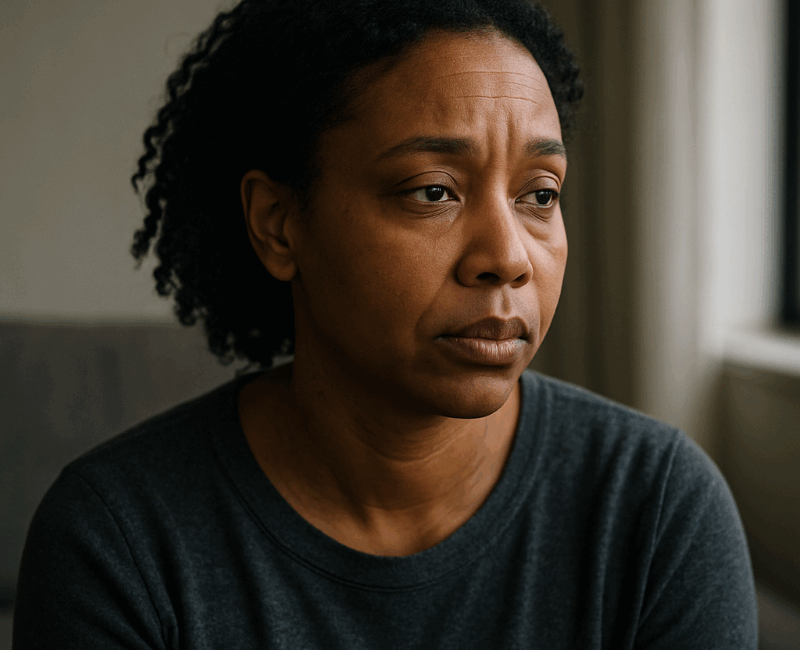

Case Study: Jane

Jane, a 42-year-old marketing executive, sought therapy for fatigue, low mood, and a persistent sense of emptiness. Although she was professionally successful and socially active on the surface—regularly attending networking events and staying connected through social media—she reported feeling “invisible” and “emotionally distant” from others. She described going home to an empty apartment and spending weekends scrolling through Instagram, comparing herself to peers who seemed to have more fulfilling relationships.

In therapy, it became evident that Jane’s loneliness was rooted in a lack of meaningful emotional connections, despite an abundance of social interaction. She struggled with vulnerability, shaped by early attachment disruptions and reinforced by a fast-paced, image-driven lifestyle. Her feelings of loneliness were not about the quantity of relationships, but the quality—no one truly “knew” her.

Through cognitive-behavioral and relational work, Jane began to challenge her beliefs about worthiness and connection. Gradually, she initiated more open conversations with close friends and joined a support group that provided deeper relational engagement. Her feelings of loneliness began to ease as she redefined what connection meant to her and learned to tolerate the discomfort of emotional intimacy.

Clinical Implications

Loneliness skews cognitive processing, leading individuals to misread social cues and withdraw further. In therapeutic settings, these distortions must be addressed, often requiring a blend of cognitive restructuring, narrative therapy, and sometimes existential exploration.

Loneliness skews cognitive processing, often leading individuals to interpret neutral or even positive social cues as signs of rejection or disinterest. These cognitive distortions—such as “I’m not likable” or “No one truly cares about me”—form a negative feedback loop that deepens isolation. Cognitive restructuring, a core element of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), helps clients identify, challenge, and reframe these maladaptive beliefs. By testing these assumptions against real-life experiences and developing more balanced thinking patterns, clients can begin to perceive social situations more accurately and approach relationships with greater confidence.

Narrative therapy adds a valuable dimension by allowing clients to re-author their personal stories about connection, worthiness, and identity. Many individuals experiencing loneliness carry internalized narratives shaped by past relational trauma, rejection, or societal messaging. For example, a client like Jane may hold a narrative of being “too much” emotionally or “not enough” to sustain meaningful relationships. In therapy, these stories can be externalized and deconstructed, creating space for alternative, more empowering narratives that support authentic connection and belonging.

In some cases, existential exploration becomes essential—particularly when loneliness touches on deeper themes of meaning, mortality, and human isolation. Clients may grapple with the idea that even in the most intimate relationships, a fundamental aloneness persists. Exploring these themes can help clients normalize the existential dimension of loneliness while also reconnecting them with personal values, purpose, and the agency to seek meaningful engagement. This work does not seek to eliminate loneliness entirely, but to integrate it as a human experience that can prompt growth, creativity, and deeper relationships.

Together, these therapeutic approaches address the multifaceted nature of loneliness: its cognitive distortions, its embedded personal narratives, and its existential weight. For clinicians, the task is not only to reduce the distress of loneliness, but to help clients build lives rich with authenticity, connection, and meaning.

As clinicians, we must assess loneliness not just as a symptom but as a central psychological experience. Jane’s story underscores the importance of helping clients move beyond performative relationships to cultivate genuine emotional intimacy—a powerful antidote to modern disconnection.

Leave a Comment